Phasics

- Wavefront, MTF and QPI measurement solutions

- Products

- Applications

- Markets

- Company

- Contact us

Dec. 15, 2025

What is an Optical Atomic Clock?

An optical atomic clock is a high-precision timing system that references the optical transition frequency within an atom or ion. Unlike traditional cesium atomic clocks, which operate in the microwave regime, optical clocks utilize transition frequencies approximately five orders of magnitude higher (

Among the various implementation architectures, the Trapped-Ion Optical Clock is one of the most accurate. In this setup, a single ion is stably confined within a Paul trap, laser-cooled to near its motional ground state, and interrogated by an ultra-narrow linewidth clock laser. This optical frequency is then measured and linked to other standards via an optical frequency comb.

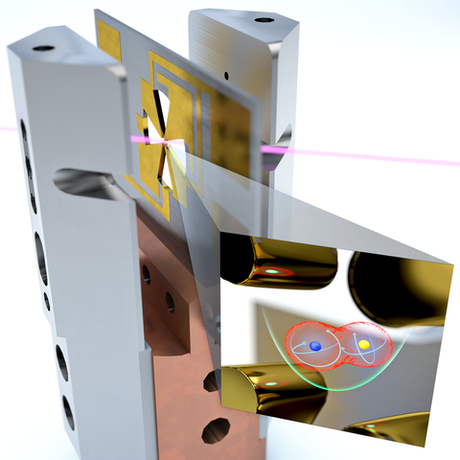

Figure 1: The NIST Quantum Logic Optical Clock is a premier type of optical clock and currently one of the most precise timing systems in existence. The image shows its core component : the ion trap (gold structure with a cross-shaped aperture) used to stably confine the ions. The inset visualizes the aluminum ion (blue), which provides the clock's "ticking" reference, co-trapped with a magnesium ion (yellow) used for sympathetic cooling and quantum logic readout. Image Credit: S. Burrows / JILA

Experimentally, trapped-ion optical clocks share the same physical platform as trapped-ion quantum computing. Both rely on electric fields within a Paul trap for confinement, ultra-high vacuum environments, and precise laser cooling and manipulation. The distinction lies in their objectives: quantum computing research focuses on using laser pulses to execute controllable quantum logic gates, whereas optical clocks utilize the same ion systems to measure and lock to an intrinsic, ultra-narrow optical transition, thereby establishing a natural standard for time and frequency.

This connection is not accidental; it reflects the universal capability of trapped-ion systems to achieve extreme precision in optical control at the quantum level. However, this demand for precision means both fields are highly sensitive to laser wavefront quality, phase stability, and injection geometry. Aberrations from vacuum windows, slight deviations in beam angle or position, thermal drift, and micro-vibrations can all translate into risks regarding frequency shifts and reproducibility.

Industry Updates: Pushing the Limits (2025)

In early 2025, BIPM/CCTF updated the roadmap and standards for the redefinition of the second. The latest technical documents establish quantifiable thresholds for entering the redefinition phase: Optical frequency standards must outperform cesium clocks by two orders of magnitude; At least five independent systems must be in continuous operation; Traceable data must be provided for over one year, with a capability for continuous reliable operation exceeding 10 days. These criteria are now being used by National Metrology Institutes worldwide to benchmark the long-term stability and consistency of their own optical clock systems.

In June 2025, a consortium involving ten optical clocks across six nations (Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the UK, and Japan) completed a 45-day joint comparison campaign. This marked the first successful demonstration of high-consistency frequency transfer over long links and between different devices, validating the feasibility of engineering and deploying networked optical clocks.

In July 2025, NIST announced its new generation Aluminum-ion (Al⁺) quantum logic clock. The system has pushed the "significant digits" of system uncertainty into the10⁻¹⁹

Figure 2: A NIST physicist holds the newly improved ion trap for the Aluminum-ion clock. Image Source: R. Jacobson / NIST

The "Hidden Challenges" and PHASICS SID4 / SID4-HR

While the optical system of a trapped-ion clock may appear stable, it faces a series of "hidden challenges" that are difficult to quantify yet determine the upper limits of performance:

In trapped-ion optical clock experiments, many performance bottlenecks stem not from quantum manipulation itself, but from difficult-to-quantify subtle errors in the optical path. PHASICS SID4 / SID4-HR wavefront sensors provide a reliable, quantitative solution for these "invisible but critical" issues.

How PHASICS Supports Quantitative Optical Control

The SID4 series wavefront sensors can capture the complete wavefront and intensity profile in a single exposure. It converts low-order and high-order Zernike aberrations, beam pointing stability, and field distribution changes into verifiable engineering metrics.

During the alignment phase, researchers can use single-shot measurements to directly assess the alignment precision of cooling, repump, and clock beams. During long-term operation, this data establishes a stability baseline to monitor drift trends.

The system allows for measuring the phase consistency of cooling, repump, readout, and clock wavelengths along the actual injection path. This is particularly valuable for experimental realities involving compact or micro-fabricated ion traps.

Quantitative results from SID4 / SID4-HR can be integrated with external phase-locking loops or adaptive optics closed-loop systems to suppress slow drifts and maintain consistency over long periods.

PHASICS is collaborating with leading international laboratories across various application scenarios.

We invite you to stay informed on the latest advancements in optical metrology, quantum control, and wavefront sensing research, as well as new applications of PHASICS technology in quantum computing.

If you have specific measurements or control requirements, we welcome your inquiries. You can connect directly with our technical sales personnel by visiting our contact page.

Related Reading: Trapped-Ion Quantum Computing: Laser Control and Measurement of Quantum States

References: